Unlike the strict goal of price stability adhered to by the European Central Bank or a focus on inflation and full employment pursued by the Federal Reserve, Asia’s central banks have to consider everything from currency stability to the welfare of their citizens, according to Bloomberg.

As the world’s top economists converge on the U.S. Federal Reserve symposium in Jackson Hole, here’s a look at the policy priorities, or mandates for Asia-Pacific’s biggest central banks:

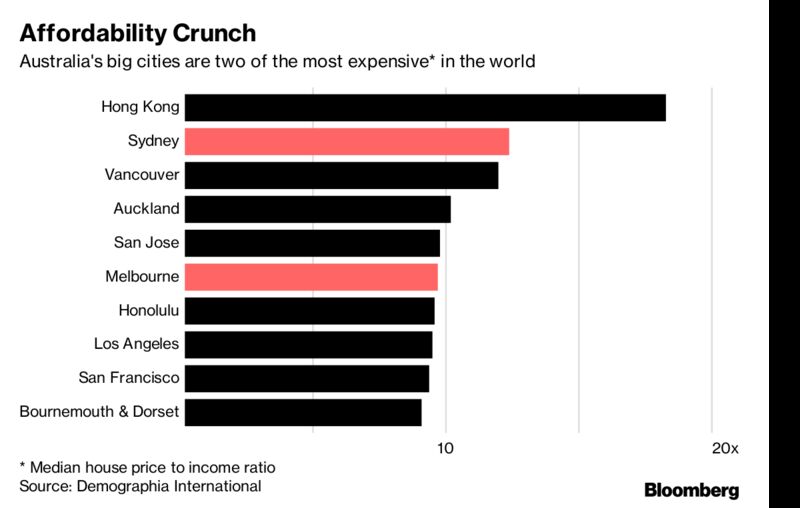

Australia:

The Reserve Bank of Australia has a dual mandate of maintaining stability of the currency and full employment. Both goals support its aim to control inflation over the medium-term. RBA Governor Philip Lowe has said his team are not "inflation nutters." But the central bank is also guided by an obscure piece of legislation dating back to World War II: a rarely-discussed third objective of the economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia. That’s increasingly topical as the nation’s house prices soar.

China:

The People’s Bank of China has four mandated objectives. To maintain price stability, boost economic growth, promote employment and broadly maintain the balance of payments. At the same time the PBOC is also tasked with promoting financial reform, liberalizing the economy and the encouragement of financial-market development. Governor Zhou Xiaochuan described the latter items as "dynamic objectives" in a speech at International Monetary Fund in June 2016.

"The choice of a multi-objective central bank has to do with China’s circumstances as a transition economy," Zhou said during the speech. "At that stage of transition from central planning to a market economy, carrying out financial reforms as well as making the financial system healthy and stable may even override the conventional objective of price stability."

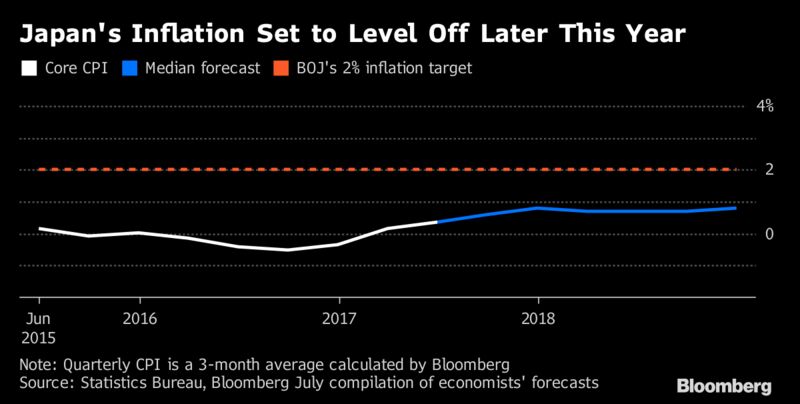

Japan:

The Bank of Japan Act, which took effect in 1998, states that the BOJ’s mandate is to keep both inflation and the financial system stable. The latter has historical resonance given the country’s economic collapse in the 1990s amid a mountain of bad debt. After more than a decade of deflation, the BOJ adopted a 2 percent inflation target in January 2013.

While the central bank can argue it has maintained banking stability, it remains a long way from reaching the price target. Kuroda said last month it’s “regrettable” the bank has to push back its forecast. Most economists surveyed by Bloomberg don’t think the bank can meet the goal.

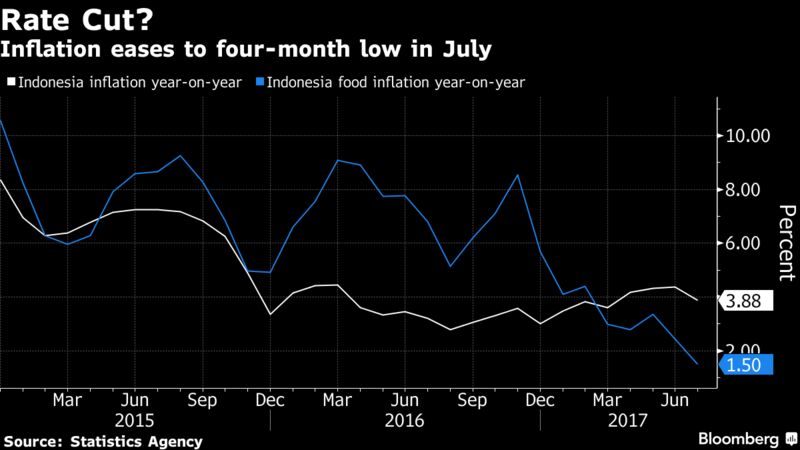

Indonesia:

Indonesia’s central bank is a currency watcher. Bank Indonesia has a key role in achieving and maintaining the stability of the rupiah, including through the use of monetary policy to manage inflation. The central bank coordinates its inflation management with the government through the use of a target band, currently 3 to 5 percent. The bank must also manage the rupiah’s exchange rate against foreign currencies.

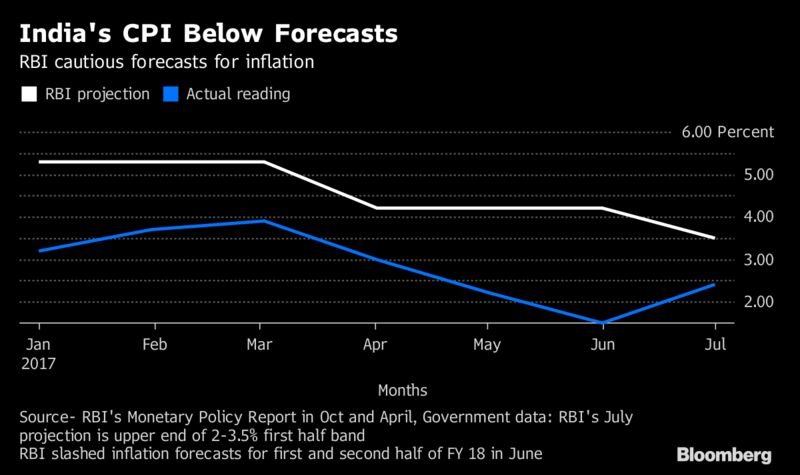

India:

After years of debate the Reserve Bank of India formally adopted a new policy mandate in early 2015 to keep inflation over the medium term at 4 percent, within a 2 percent range either side. A six-member committee, comprising of three central bankers and three external economists meet every two months to decide on rates.

The RBI’s inflation model consists of four variables: the output gap, the Phillips curve which assesses the impact of unemployment, the Taylor rule for short-term interest rates that also guides several global central banks, and interest rate parity through exchange rates.

The RBI cut rates to their lowest levels in seven years in August. In June, headline inflation slowed to a record low of below 2 percent.

South Korea:

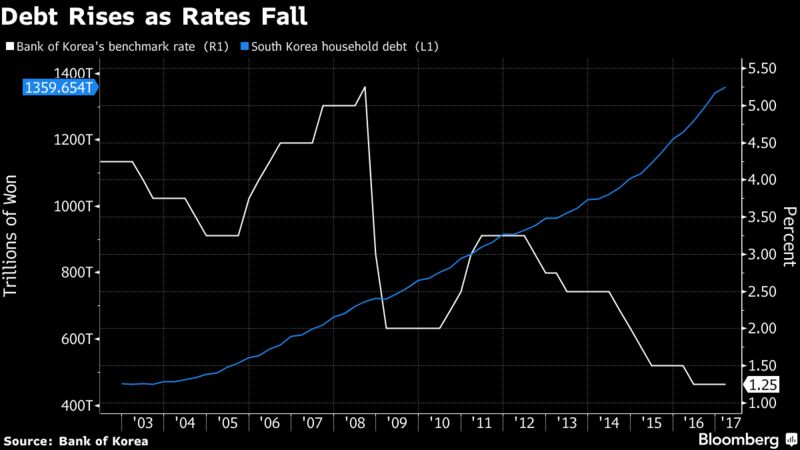

The Bank of Korea’s two main monetary policy objectives are price stability and financial stability. The latter is significant in a nation grappling with a surge in debt. The BOK has an inflation target of 2 percent for 2016-2018. The governor is forced to explain to the public if inflation trails, or exceeds the target by more than 0.5 percentage points for six straight months.

What does it all mean?

Ahead of plans by the Federal Reserve to shrink its $4.5 trillion balance sheet, some investors caution that the move poses considerable uncertainty for Asia. The worry is that any Fed tightening will suck capital away from Asia and send currencies lower. That would prompt central banks to respond through either defending their currencies or hiking interest rates.

To be sure, maintaining price stability is a priority. Inflation is an especially sensitive topic in a region where developed and emerging economies are vulnerable to big swingsin food and energy prices. Whichever way the Fed balance sheet plays out, Asia’s central bank governor have an array of options on how to respond.

eghtesadOnline